Author(s) : UNHCR

Publication Type : Report

Date of publication : August 2017

Link for the original document

*Wathinotes are excerpts from publications chosen by WATHI and conform to the original documents. The reports used for the development of the Wathinotes are selected by WATHI based on their relevance to the country context. All Wathinotes refer to original and integral publications that are not hosted by the WATHI website, and are intended to promote the reading of these documents, which are the result of the research work of academics and experts.

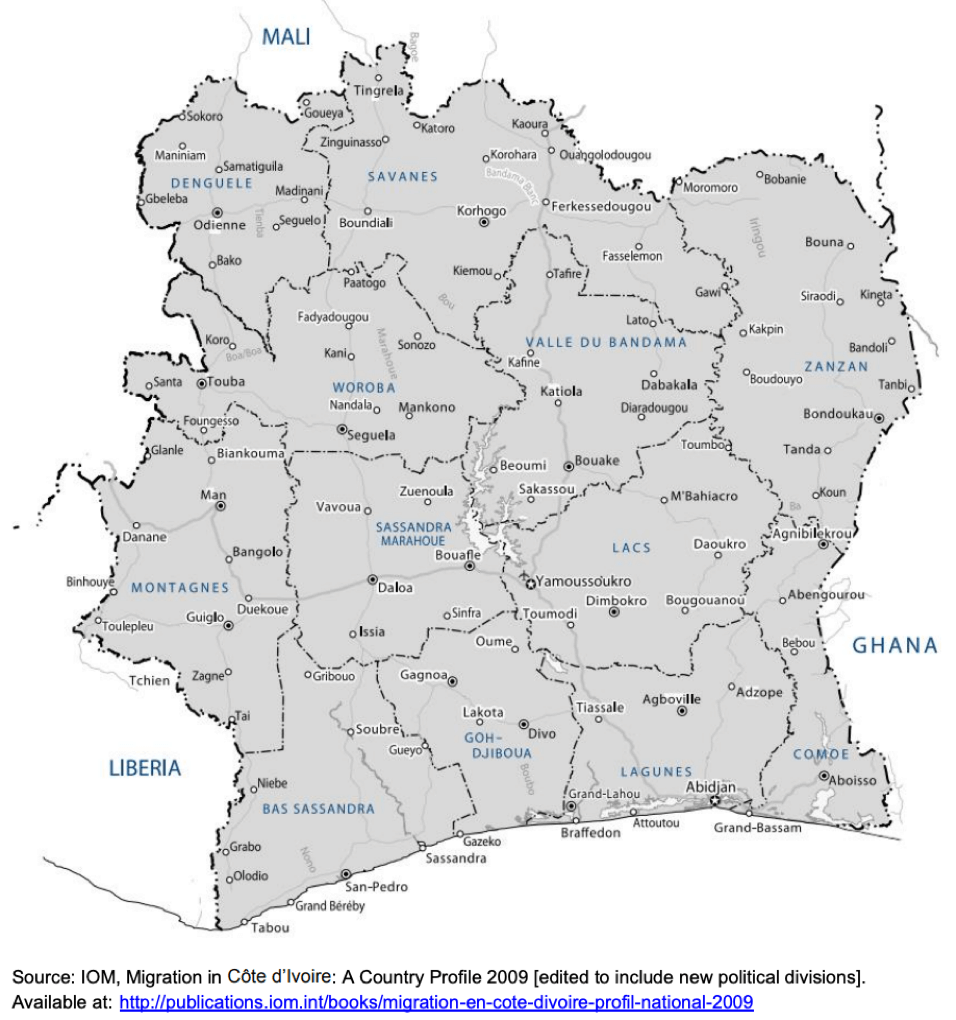

Côte d’Ivoire is a country in Western Africa, bordering Ghana in the east, Burkina Faso and Mali in the north, Guinea and Liberia in the west, and the Gulf of Guinea in the south. It has a population of 23,295,302 and covers an area of 322,463 sq. km. The official language is French, although a large number of native dialects are also spoken. (CIA, 11 February 2016).

In 1990, the first multiparty presidential elections were held and Houphouët-Boigny was once again elected president. He held power until his death, in 1993, when he was succeeded by Henri Konan Bédié. (BBC News, 5 May 2015).

Côte d’Ivoire is a country in Western Africa, bordering Ghana in the east, Burkina Faso and Mali in the north, Guinea and Liberia in the west, and the Gulf of Guinea in the south. It has a population of 23,295,302 and covers an area of 322,463 sq. km

“Houphouët-Boigny was able to maintain, for the most part a peaceful one party regime in his relatively prosperous nation (being the world’s largest exporter of cocoa), while remaining on good terms with both France and its African neighbors. » “his successor, Henri Konan Bédié, was less focused on avoiding tensions” and “stressed the concept of ‘Ivority’. This was mainly to hurt his rival, Alassane Ouattara, whose father was from Burkina Faso.”

In 1999, a military coup led by General Robert Guéï overthrew Bédié. In the months following the coup, a highly contested election took place, reaffirming Guéï’s victory over the opposition candidates, namely Laurent Gbagbo, leader of the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI), and Alassane Ouattara, banned from the presidential election because of his foreign parentage. Henri Konan Bédié, was less focused on avoiding tensions” and “stressed the concept of ‘Ivority’. The First Ivorian Civil War lasted from 2002 until 2007. Minority Rights Group (MRG).

In 2010, new elections were organized, as explained by a May 2013 report submitted to the UN Human Rights Committee. the population of Côte d’Ivoire is estimated at 23,295,302 as of July 2015. Population growth is estimated at 1.91% in 2015 and adds that life expectancy in the country lies at 58.34 years – 57.21 years for males and 59.51 years for females. (CIA, 11 February 2016).

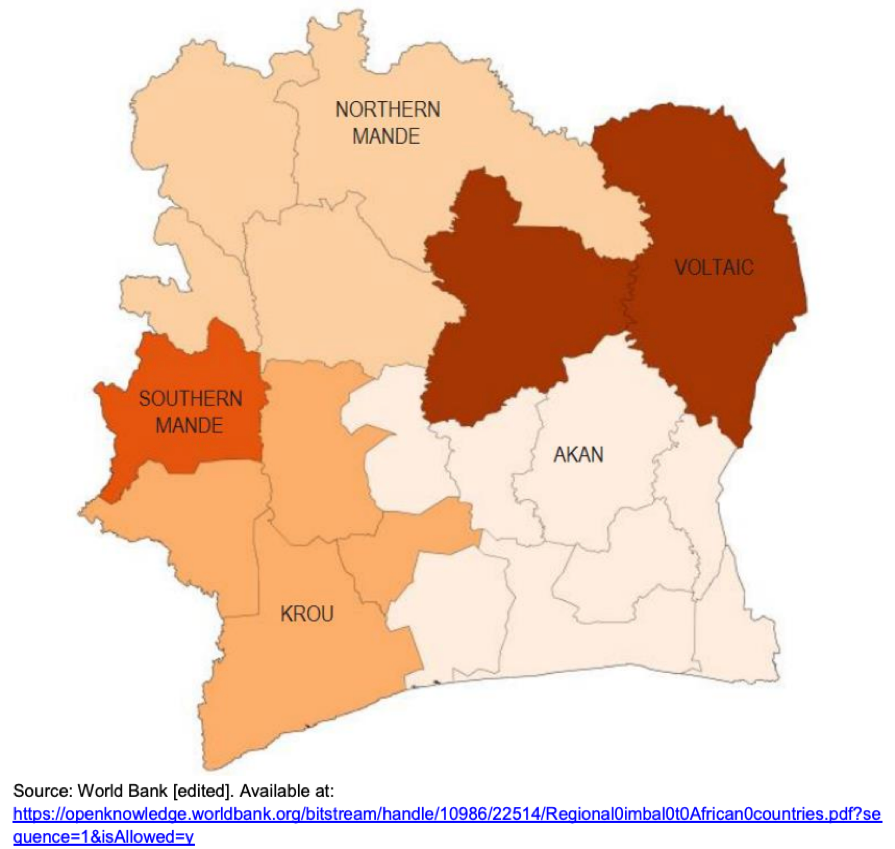

Côte d’Ivoire is a highly ethnically diverse country with more than 60 indigenous ethnic groups, belonging to five main socio-cultural or ethno-linguistic groups: Akan (32.1 percent), Voltaic or Gur (15 per cent), Krou (9.8 per cent), Northern Mandé (12.4 per cent) and Southern Mandé (9 per cent). (CIA, 11 February 2016).

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) explains the following : “Members of ethnic communities from the northern and central parts of the country are generally assumed to be pro-Ouattara. These include the Bambara, Malinké and the northern Manding or Mandé grouping (also known as Dioula). Members of ethnic communities from the south and west are generally assumed to be pro-Gbagbo. Groups in the west and centre-west which are assumed to be pro-Gbagbo include the Krou (subgroups of which include the Guéré, Wobe, Godié and the Bété), and the southern subgroups of the Akan, including the Attié, Ebrié, and Guro.” (UNHCR, 15 June 2012, p. 16)

« Resulting from extensive international migration flows, a large proportion of the people in Côte d’Ivoire is of foreign origin. From the early 1940s, the French colonial administration organised the transfer of forced labour from the Upper Volta, today’s Burkina Faso, to the cocoa and coffee plantations in the southern parts of Côte d’Ivoire. »

A July 2015 report by Minority Rights Group (MRG) notes that Côte d’Ivoire “became the most common destination for West African migrants following its independence in 1960 due to perceptions of its wealth and stability.”

« Resulting from extensive international migration flows, a large proportion of the people in Côte d’Ivoire is of foreign origin

As reported by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Fact book, 42.9% of the population identify as Muslims, 17.2% as Catholics, 11.8% as Evangelicals, 1.7% as Methodists, 3.2% other Christians, 3.6% as animists, 0.5% belongs to other religion and 19.1% belongs to none. (CIA World Book, 2017, acceesed at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/geos/iv.html).

With respect to the inequalities across religions, the same source also notes that “it emerges that Christians, as expected, are doing relatively better than Muslims in terms of having access to electricity. Yet, the difference between Christians and Muslims is moderated by the fact that a relatively higher proportion of Muslims lives in urban areas.” (World Bank, 2015, p. 21)

An undated article by the Rural Poverty Portal (RPP), a website powered by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), also notes: “Lack of access to land is a major cause of rural poverty. Small-scale producers of food crops have access to about half the amount of land available to large-scale producers of export crops. Education levels among food crop producers are low, and their access to technology is limited. In zones where population pressure and environmental degradation have reduced overall access to productive land, women are generally the first to feel the negative effects.” (RPP, n.d.)

In its 2016 World Report, Human Rights Watch (HRW) states: “Security forces continued to plunder revenues through smuggling and parallel tax systems on cocoa, timber, diamonds, and other natural resources. In its April 2015 report, the UN Group of Experts, appointed by the UN Security Council to monitor the sanctions regime in Cote d’Ivoire, identified several army officers involved in the illicit exploitation of natural resources, including gold and cocoa.

“it emerges that Christians, as expected, are doing relatively better than Muslims in terms of having access to electricity. Yet, the difference between Christians and Muslims is moderated by the fact that a relatively higher proportion of Muslims lives in urban areas.” (World Bank, 2015, p. 21)

Extortion by security forces at illegal checkpoints remained an acute problem, particularly on secondary roads in rural areas. A specialized anti-racket unit has been undermined by inconsistent financial support from the government and the failure of the military tribunal to consistently prosecute perpetrators.” (HRW, 27 January 2016).

Corruption in Côte d’Ivoire is endemic and permeates all levels of society, which is reflected in the country’s poor performance in most areas assessed by governance indicators.

“Furthermore, the government has done too little to address corruption in the justice sector. Despite Ouattara’s 2011 promise that corrupt judges would be fired, Ivorian jurists told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any judges being disciplined or prosecuted for corruption since 2012.” (HRW, 8 December 2015, p. 7)

Corruption in Côte d’Ivoire is endemic and permeates all levels of society

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Criminality – and armed robbery in particular – has been an acute problem in Côte d’Ivoire for years, particularly in the northern and western regions. Officials from the European Union, the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, and Ivorian human rights groups have repeatedly expressed concern about the problem.” (All Africa, 15 December 2014).

Amnesty International (AI) also reported deaths related to toxic waste: “In July [2016], the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) undertook an environmental audit of the lasting impact of the 2006 dumping of over 540,000 litres of toxic waste in Abidjan. The waste was produced by the multinational oil trading company Trafigura. The results were expected in early 2017. The authorities reported that there were 15 deaths while more than 100,000 people sought medical attention after the dumping including for serious health issues like respiratory problems.

The authorities had still not assessed the long-term risks to individuals of exposure to the chemicals in the waste and had not monitored victims’ health. Many victims had not received any compensation payments and compensation claims against the company continued.” (AI, 22 February 2017)

Despite the arms embargo, an article by the Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN) reveals the following: “Angola, China, Belarus, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Israel sold weapons to the Ivoirian government between 2002 and 2003, according to the report.

The authorities had still not assessed the long-term risks to individuals of exposure to the chemicals in the waste and had not monitored victims’ health

According to a May 2013 submission by Côte d’Ivoire to the UN Human Rights Committee, Côte d’Ivoire “is a secular, democratic and social State” which “respects human rights and public freedoms in a spirit of public peace, national solidarity and justice.” (UN Human Rights Committee, 21 May 2013, p. 7). According to a December 2015 UN Security Council report, “the security situation in Côte d’Ivoire remained generally stable but fragile.” (UN Security Council, 8 December 2015, p. 7).

Côte d’Ivoire “is a secular, democratic and social State” which “respects human rights and public freedoms in a spirit of public peace, national solidarity and justice.”

Land and ethnocentric politics have proven an explosive cocktail over the last 15 years in Côte d’Ivoire, particularly in the country’s volatile west. Land dispossession remains a key driver of inter-communal tensions and local-level violence between ethnic groups in western Côte d’Ivoire. In March, violent intercommunal clashes between pastoralists and farmers in Bouna, in the northeast, left at least 27 people dead and thousands more displaced.

The security situation in Côte d’Ivoire remained generally stable but fragile

According to a 2011 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report entitled “They Killed Them Like It Was Nothing”: « The post-election violence was the culmination of a decade of impunity for serious crimes. »

Land and ethnocentric politics have proven an explosive cocktail over the last 15 years in Côte d’Ivoire, particularly in the country’s volatile west

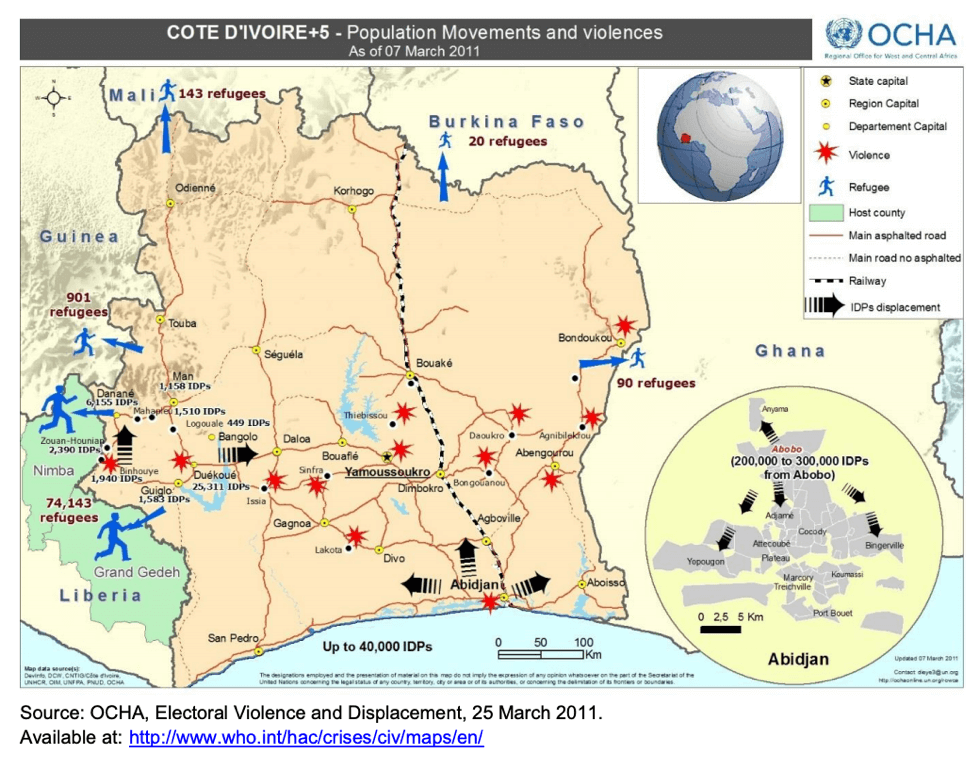

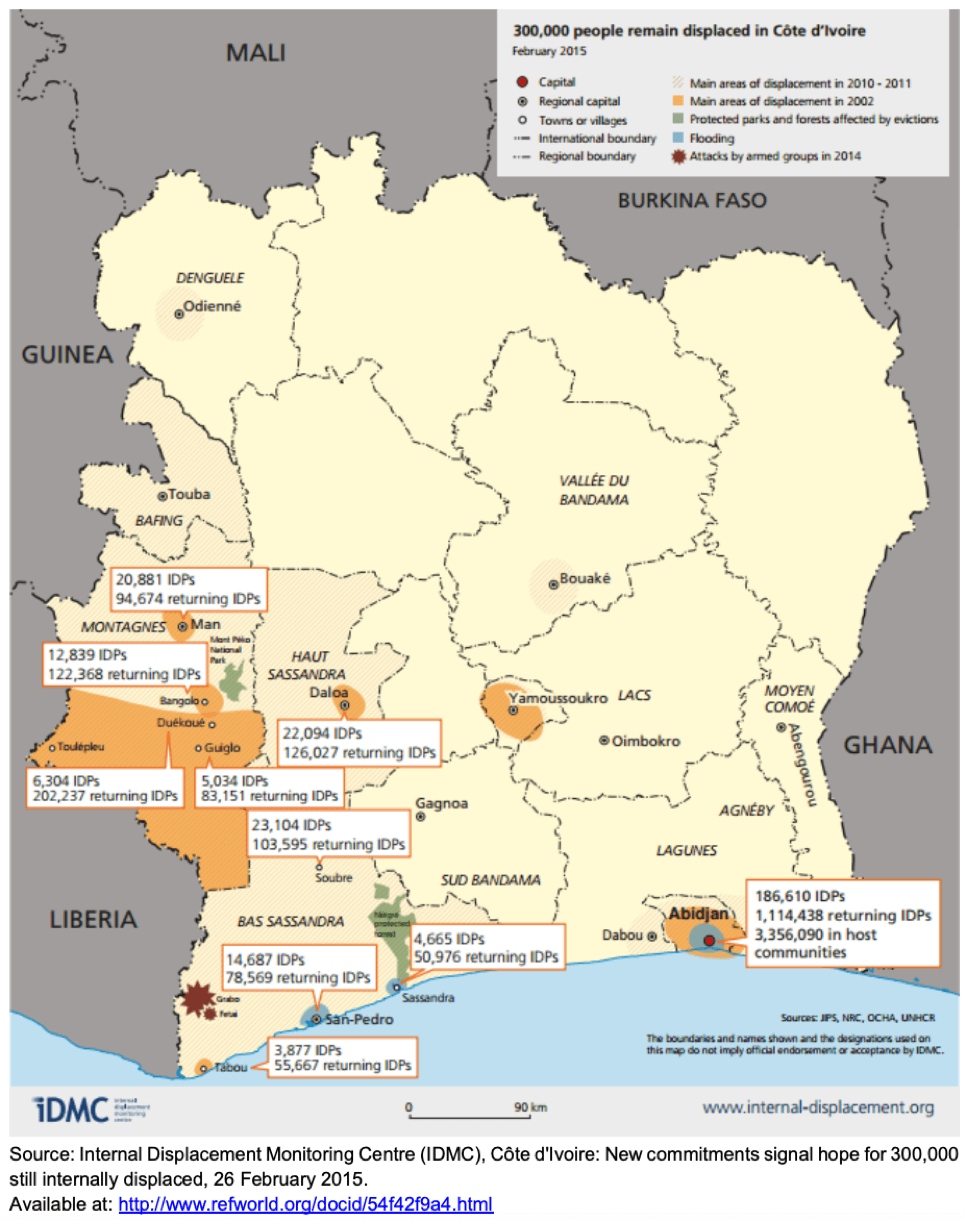

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), “the profiling report revealed that more than 2.3 million people had been internally displaced since 2002, of whom 300,889 were still living in internal displacement as of mid-2014. Sixty-two per cent of remaining IDPs were living in Abidjan, where most said they planned to integrate locally. The capital also hosts more than half of the country’s returning refugees and returning IDPs.” (IDMC, 26 February 2015).

Several commanders implicated in serious human rights abuses remain in key positions in the security forces

“Since 2015, a total of 24,134 Ivorian refugees have returned with support from UNHCR and its partners, 23,417 of whom from Liberia and 717 from other countries, such as Togo, Mali and Senegal (as of 31 May 2017). Since the beginning of 2017 alone, UNHCR has facilitated the safe and dignified return of 3,762 Ivorian refugees. Today, some 30,000 Ivoirian refugees are still exiled in other countries in Africa.” (UNHCR, 31 May 2017, p. 3).

« Members of the security forces including soldiers, gendarmes, and police perpetrated numerous serious human rights abuses, including mistreatment and torture of detainees, sometimes to extract confessions; extrajudicial killings; rape; and extortion. Several commanders implicated in serious human rights abuses remain in key positions in the security forces. ».

The death penalty was officially abolished in Côte d’Ivoire following the 2000 Constitution.

According to a May 2013 submission by Côte d’Ivoire to the UN Human Rights Committee, “Article 9 of the Ivorian Constitution enshrines freedom of thought and expression, particularly freedom of conscience and of religious or philosophical opinion.” (UN Human Rights Commit. Homosexuality is reportedly legal in Côte d’Ivoire; nonetheless, public indecency with a same sex partner is criminalized. (IRRI, n.d.).

Article 9 of the Ivorian Constitution enshrines freedom of thought and expression, particularly freedom of conscience and of religious or philosophical opinion

According to the United States Department of State’s trafficking of persons 2016 report, “Cote d’Ivoire is a source, transit, and destination country for women and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking.” (USDS, June 2017, p. 41). The health care infrastructure has been weakened, particularly in the northern regions of the country, which are still undergoing reconstruction. […] In Côte d’Ivoire, where HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria are primary health concerns, access to care is essential.

Commenter